2019 - THROWING A CURVED BALL

Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity — a theory that offered radical new concepts of time and space, including the existence of black holes and the concept of dark matter — was proven beyond doubt on an expedition to the Kimberley in 1922.

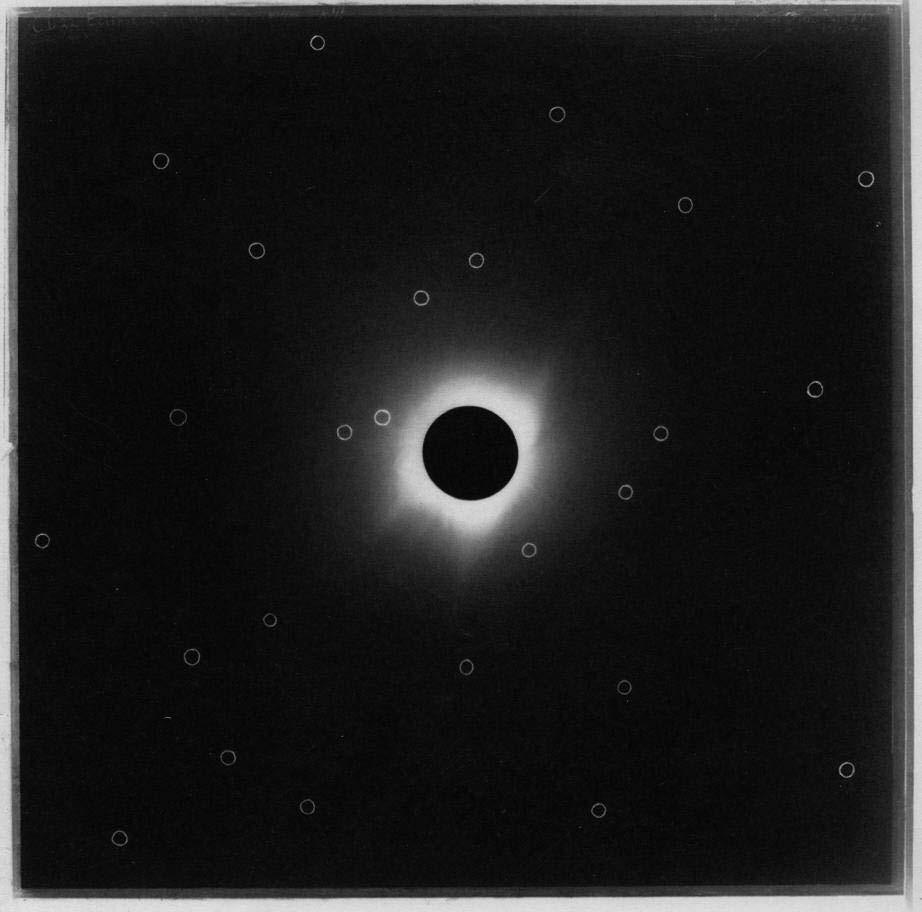

On 22 September 1922, a team of astro-scientists captured images of a total eclipse of the sun at Wallal, 200 miles south of Broome, confirming one of the most exciting scientific theories of our time and setting the scene for the litany of discoveries in quantum physics that followed.

In 1915 Einstein contended that objects such as our sun caused a warping of ‘spacetime’. He suggested that this curvature of spacetime could be proven if we could see the effect it had on waves of light as they travelled past the sun. Witnessing the curvature of starlight would only be possible during a total eclipse.

Although the shadow of the eclipse travelled across the entire continent of Australia, Wallal was considered be the ideal place to observe the event. On 28 August, a contingent of over 20 scientists sailed from Fremantle to Broome on board the SS Charon. In Broome, 35 tons of equipment, including a 40-foot telescope, was transferred to the schooner Gwendoline and, with the steamer Governor Musgrave, the party sailed south to Wallal to await the eclipse.

The eclipse lasted 5 minutes and nineteen seconds, long enough for scientists to capture the vital images on a series of glass plates. Some plates were developed at Wallal and the remainder in Broome: the American team led by WW Campbell from the Lick Observatory set up a darkroom in the gasoline engine room of the Broome Coastal Radio Station (now the Broome Bowling Club), where about 80 star images were carefully measured with ‘Einstein’s measuring microscope’.

Unlike images obtained during the 1919 eclipse in Brazil, which were of poor quality and showed few stars, the clear images from Wallal and the precision of the initial measurements ‘exceeded all expectations’. The Broome community helped the visiting scientists celebrate — an evening of music, supper and dancing was held at the Magistrate’s residence, gaily festooned with Chinese lanterns, and guests witnessed a celebratory corroboree performed by Aboriginal men and women, their bodies daubed with paint, traditional headdresses standing out against the night.

In April 1923, the British Royal Astronomer was formally advised by Campbell that the results of the Wallal solar eclipse expedition were conclusive and need not be repeated. Einstein was right!